Glint of dawn

3Dlabs is now a vanishing brand of professional 3d graphics, but once upon a time, it was a leading company in the field. Already in 1985, the founding British duo boldly set out to build the fastest 3d engine. They turned some heads, but true fame came in 1994 with the 300SX chip, a low-cost texture mapper that defined the standards of 3D acceleration. First, it should be noted that the Glint 300SX was designed in the Pixel division of Du Pont, which was working with graphics for 10 years and became a known name in the 3d world, especially on Sun systems. With advanced hardware and primarily software, Du Pont Pixel was quite a competitor for Silicon Graphics' solutions. Just after announcing the development of a relatively cheap and feature-packed 300SX chip, Du Pont agreed to sell the Pixel division to a fresh startup 3Dlabs, and most of the important people transferred as well. Which makes me wonder if Dupont regretted it later. Or is it necessary to have a specialized graphics company to be successful in 3d technologies? 300SX professional 3D graphics cards were spreading in scale unheard of before 1995. This site is all about gaming cards, but I found it impossible to write about 3Dlabs without mentioning influential chips like the Glint. The first single chip 3d accelerator with texture mapping pushed prices down to around $2000, which was highly affordable in the workstation world.

First of the line

The 300SX had all the rendering, fragment processing, and rasterisation operations of OpenGL on a single chip, "full speed" Z-buffering, dithering, and anti-aliasing. At its 50 MHz frequency, it claimed a rendering speed of 300,000 Gouraud shaded, depth-buffered, and anti-aliased polygons per second. Two clocks are needed to fill one smooth shaded pixel, and the rate is halved with depth buffering. 32-bit datapath is maintained from the beginning of the pipeline to the end. The chip provided complete 2D and 3D acceleration in true color, PCI interface, and, along with LUT-DACs, support for palletized textures. Frame buffer used 64-bit VRAM interface and optional DRAM memory with 48-bit bus could store depth buffer, masks, and other graphics data, except textures. Many technologies similar to buzzwords of our time appeared already back then. Fujitsu Microelectronics has developed a proprietary technology called PixelBus, which allows you to link multiple Glint cards together to get increased speed. PixelBus also supports a synchronized output mode for panoramic display systems. Relatively cheap 300SX was a great success; of course 3Dlabs continued improving the architecture. The first step should have been the GLINT 300TX with texture mapping from local memory. This was to be the main goon for arcade developers. At the time, 3Dlabs did not shy away from games as API work shows- Reality Lab and BRender support was prepared. The 300TX claimed Gouraud shaded, depth buffered, window clipped, stippled, dithered, and alpha tested rendering performance with 24-bit colors of 300K 25 pixel triangles per second. However, it did not materialize, at least not under that name. Another Glint product came around and it had a very different purpose.

3D Blaster VLB

In 1995, 3Dlabs targeted gamers and managed to reduce the price to a level suitable for the consumer market. Together with Creative they launched the 3D Blaster for Christmas. As the only texture mapper for VL-Bus, this card is truly special, limited to the 486 platform with the exception of rare Socket 4 and 5 boards. Thanks to great help of Gona, I can now test the card with one such motherboard and Tillamook CPU screaming at 266 MHz.

I assume Creative was eager to be the first with a consumer texture mapper, but Diamond Edge 3D arrived on the market several days before.

I assume Creative was eager to be the first with a consumer texture mapper, but Diamond Edge 3D arrived on the market several days before.

It is an add-on 3d card, but it can also accelerate GUI and several video codecs. In fact, it is required to disable the primary graphics adapter in Windows; the Blaster takes over everything. Creative felt confident even against the new 32 bit consoles, which was quite optimistic. Either way, they developed own API for 3D accelerated games, Creative Graphics Library. And Creative 3D Blaster VLB would be the first card supporting it. Memory capacity had to be squished to achieve consumer-friendly pricing. There is 1MB DRAM for textures and Z-buffer, and 1MB VRAM frame buffer. Obviously, one cannot expect much jaw-dropping 3d within such limits. Maximum resolution at 16-bit depth is 640x400. Since many accelerated games after the release of Voodoo Graphics did not support anything below 640x480, the 3D Blaster VLB is one of the prime victims, unable to even start those. Rendering inside a window is supported, but since the desktop also takes its part of the capacity, the window is limited to 320x240x16 resolution. Normally, I would not comment on 3d acceleration in window, but there is a performance anomaly with the card: full-screen is slower. That is the opposite of what should be happening and a clue to how much performance the Direct3D driver can leave on the table. The latter of the two known d3d drivers was used for the tests. Theoretical fill rate of 25 megapixels/second is just so-so for 640x400x16. That is the announced fillrate which probably expected 50 MHz clock. But take a look at the crystal behind the Glint. 40 MHz feeding it directly, I have no doubt this is the frequency, unfortunately lower than expected. 20 megapixels is a true value and multiple times higher than real performance I've measured. What can the Gaming Glint, familiarly nicknamed "Gigi", actually do?

Architecture

The games-tuned GLINT chip promised arcade-quality 3D performance and texturing with true perspective correction and filtering, fogging, blending, translucency, and stencils at the minimum possible cost. Colors are limited to 8 or 16 bits. Geometry performance with texturing was reduced by one third; the speed of the Glint architecture was, in general, quite sensitive to features used in rendering, but this gaming part is reduced from the very first stages on one hand and built with texturing as a necessity on the other. The Gouraud shading has a measurable performance impact even without texturing. That is less surprising than its limited color resolution, not quite "smooth" shaded:

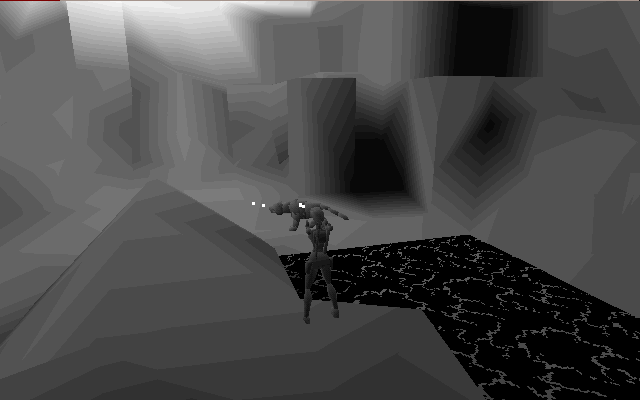

No textures are to be seen in Tomb Raider II, let's take a look at the shading instead.

Only dithering can hide the banding on darker triangles. However, this pattern can permeate the textures, engendering yet another form of disruption. And thanks to the color banding, one more flaw is obvious. The color boundaries are not aligned well with polygons at certain angles. Gaming Glint is one of those chips that has trouble with straight lines. I have never seen perspective correction have a speed impact; perhaps 3Dlabs was a bit too skimpy in this department.

That can be one reason why the speed of texturing is quite fast. Granted, the baseline framerate is not high to start with, but for a chip from 1995, this is still a nice surprise. However, the only texture format exposed to Direct3D is 5550. That means no support for transparent textures and sub-par rendition of green colors. On top of that, there is no bilinear texture filter; the magnification technique seen in CGL games does not seem to be based on interpolation.

Vertex alpha blending is absent, but vertex fog is fine. Hardware Z-buffer works as well, costing not more than 20% of the framerate.

There is a 32-bit datapath to the FPM memory. Since the card is limited to 16-bit Z-buffer and 16-bit point sampled textures, there should be no bottleneck. Then there is the dual-ported EDO video RAM for the framebuffer. However, those chips operate with only one byte, so this path is also only 32 bits wide. Although the second port makes data reads of display output "free", with a bus width that small, no framerate records can occur.

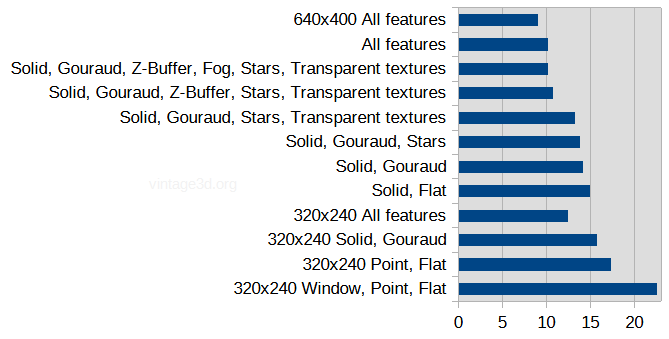

To show how it affects the speed in numbers, here are the results from PCPlayer Direct3d, a rare case of synthetic benchmark working well with the card:

The maximum framerate occurred while rendering in a window. There is a drop of ~10 % when we start actually outputting pixels, and again when the resolution is increased to 512x384. No feature is extraordinarily taxing; the most costly is depth buffering. Increasing the resolution further to 640x400 causes only 10 % slowdown.

Blasting outside of CGL

The 3D Blaster VLB promised a Direct3D driver, but when Microsoft finally released the API, there was little the Gaming Glint could do. Creative took its time with the driver and memory expansion module. That was an additional $50 to get capacity assuring d3d compatibility. As far as I know, nobody has even a picture of the module. The small fraction of games that can live with so small video memory can be divided further because some demand alpha channel outright. Sad losses are some of the most primitive 3d games like Grim Fandango or Resident Evil. A game as compatible as X: Beyond the Frontier also fails. It will be much shorter to describe games that did run. MS Flight Simulator 98, this one is a keeper. Then, the first Motoracer, if you know how to persuade it. The visuals seem to suffer from some precision issues. On the track appear a few wrongly colored pixels and sideline textures from black horizontal lines between them- is that a subpixel accuracy issue? Another game like Take No Prisoners is Mage Slayer. Same transparency issues, and look how the texture of the wall at the bottom is warped:

It is a lot worse while moving; textures aligned at angles like that to the camera are very floaty. It can get worse. In Jedi Knight the textures of weapons, characters, and pillars are warping all over the objects; they are simply not mapped correctly at all.

And the game crashes on me while leaving the very first room. Not playable. One last game that runs is Turok. It again suffers from many transparency issues and unconvincingly applied textures. Overall, the only Direct3d game of the benchmark suite that ran reasonably well was Motoracer. And that one does not even want to start easily in that way, so you can imagine what the verdict on compatibility is.

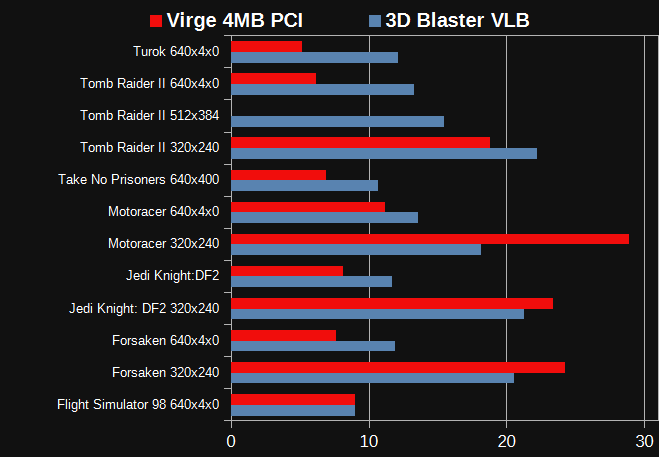

Performance

It was already revealed that this card ain't no speedster. So far, only one reviewed solution was clearly slower: first Mpact!. For comparison I picked the slowest of quite compatible cards, the original Virge by S3.

The 3D Blaster VLB is clearly the faster card. However, there are several caveats. Do remember the 3D Blaster is limited to 640x400, while the results from Virge are at 640x480, unless stated otherwise. I did the math and tried to reduce the framerates of the Blaster by 20 % to compensate for the 20 % more pixels it would need to render. Even then, the Virge would fall behind by a small margin. No compensation would help it not to get beaten heavily in minimal framerates, though. The Gaming Glint's minimal framerate is very stable, doubling that of the competitor. But that is not a big achievement when it does not perform the transparencies, alpha blending, and texture filtering as the Virge does.

Creative

Even Creative's name did not attract enough game developers to ensure that a large number of 3d-enabled titles would run on the 3D Blaster. And yes, Creative claimed several hundred high-end GLINT boards were seeded to key game developers at the beginning of 1995 and received excellent feedback on 3D Blaster's rendering quality and functionality. As I look at it, the only chip the devs could get at the time was the 300SX, which means less memory restrictions than the 3D Blaster. Only a small fraction of seeded developers come up with Gigi ports. Another revolution, like the one Creative achieved with Sound Blaster sound cards years earlier, was much harder to pull off. Even bundled games were running slowly. Consumers wouldn't risk $349 (or even higher street prices) even though there were five or six mostly attractive games bundled: early on Magic Carpet Plus, Cybersled, Azreal's Tear, NASCAR, Magic's Ballz Out!, and Flight Unlimited. Later Hi Octane! using antialiasing was added as well. For gamers, it was much safer to upgrade from a 486 than to purchase a VL-Bus 3D add-on card, which you cannot carry to your next system. Having no competition on a massive install base was just not enough to sell. Creative planned PCI version with AWE32 wavetable audio for spring 1996, and for early '97, even a version with integrated 28.8Kbps modem for multiplayer gaming. Something obviously changed their minds, which is most probably a good thing. Ambitions to dominate 3d acceleration via Gaming Glint vanished. But were competing companies that delivered their chips before Christmas 1995 doing better? Nvidia NV1 or Yamaha RPA had the same fate, 3D Blaster VLB at least had a game library containing more than several 3d accelerated games. And since Creative made CGL hardware agnostic, it is no wonder they continued the 3D Blaster brand with a PCI card based on a much more capable Vérité chip by Rendition in less than a year.

Conclusion

The attempt to create a popular 3d gaming chip by reverse engineering the Glint wasn't successful. Maybe the VLB card was the only one, because the slower systems would hide the unimpressive performance of Gigi. It was quite a project to build this system with nearly the fastest host possbible for a VLB bus, but no performance miracle has happened. The "junior" version of once formidable Glint can draw 20 frames per second at 320x240 on a good day and does not look much better than a software renderer. It is not bad among competitors of 1995, but also not good enough to make a consumer feel like they did not throw their money away. The Direct3d driver failed to extend its usefulness.

Let's see how the waterfall in Turok looks- oh, it is not even there.

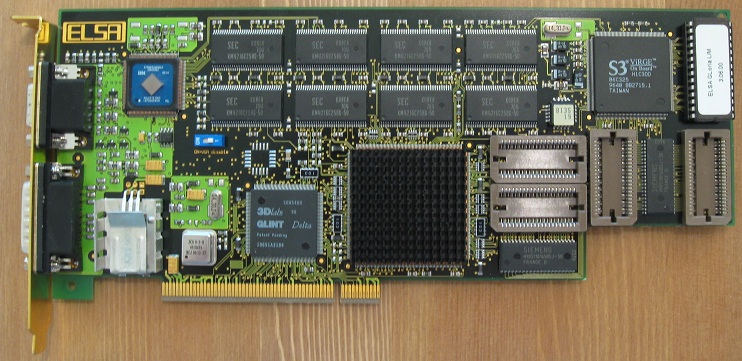

Albeit the driver effort would not go to waste. More chips were coming, and 3DLabs would again create one for professional usage and one for mainstream. In summer 1996 came high-end Glint 500TX, here is Elsa Gloria L/M:

In the center reigns monstrous 500TX, left of it coprocessor Delta, on the right Virge for basic VGA functions.

In one more year, all this functionality would be integrated into the Permedia 2 chip.

In the center reigns monstrous 500TX, left of it coprocessor Delta, on the right Virge for basic VGA functions.

In one more year, all this functionality would be integrated into the Permedia 2 chip.

Let's not skip ahead. By the end of 1996, just when the prospect of gaming 3d accelerators begins to look hopeful, 3Dlabs had first fully integrated all-around chip and was hoping for a mainstream breakthrough. It is not even named after Glint.

continue to Permedia review